10 Fascinating Facts You Never Knew About Horse Jockeys

Horse jockeys often appear effortless on the racetrack, skillfully guiding thoroughbreds to victory. However, there's a world of discipline, challenges, and untold stories beneath the surface of this demanding career. Here, we reveal ten surprising facts about jockeys that highlight just how complex and tough their profession really is.

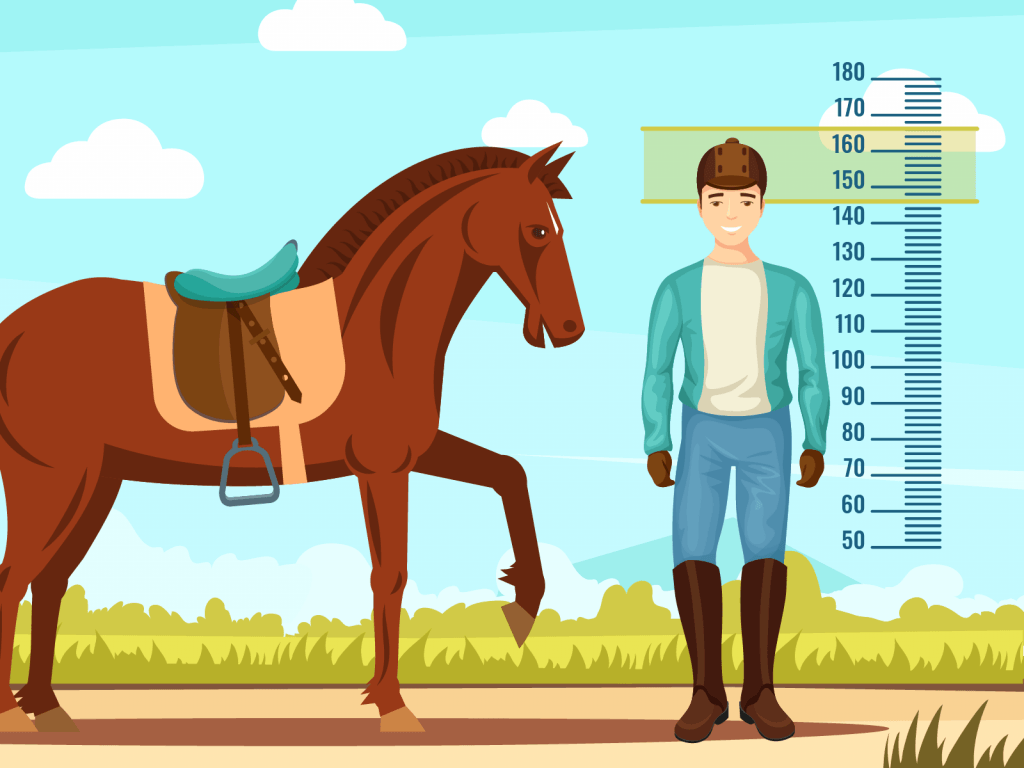

Height: No Official Maximum, But Shorter Jockeys Have an Edge

Contrary to popular belief, there is no upper height restriction for professional jockeys. Race organizers are far more concerned with weight than with stature. Despite this, shorter stature tends to be an advantage-primarily because maintaining the low weight thresholds set for races becomes much more challenging as height increases.

Take Donnacha O’Brien, for instance: standing nearly six feet tall (1.82m), he transitioned to training at just 21, unable to keep up with the stringent weight requirements despite his talent in the saddle. Traditionally, jockeys tend to fall between 4ft 10in (1.47m) and 5ft 6in (1.67m) tall. While diminutive height is favored, physical strength is also essential for maintaining control over powerful racehorses.

The Record for Tallest Jockey Defies Belief

While petite riders dominate the sport, outliers exist. Manute Bol, a former NBA basketball player standing at 7ft 7in (2.31m), holds the title of tallest person to ride in a competitive race-a singular appearance for charity in Indiana. Australia’s Stuart Brown, at 6ft 3in (1.87m), and Britain’s Patrick Sankey, at 6ft 7in (2.01m), both raced successfully despite additional hurdles with weight and balance.

Being tall means having to work much harder to meet weight requirements, and most such jockeys compete at a significant disadvantage, physically speaking, compared to their shorter rivals. Even top-level jockeys find that natural body size can ultimately force them from the saddle.

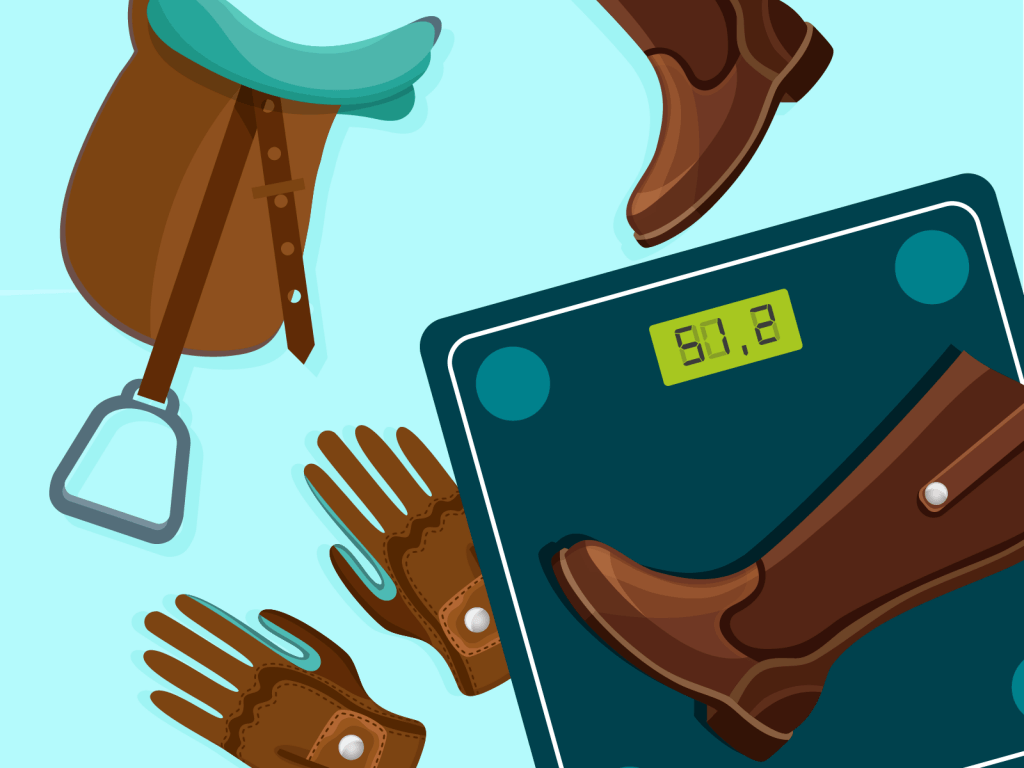

Weight Rules Trump Height-And Jockeys Must Constantly Meet Strict Standards

Though height is not regulated, jockeys are required to meet precise weight standards that are set according to the conditions of each individual race. These standards might be static or adjusted in handicaps based on the competitive rating of the horse. In such cases, the highest-rated horse carries the most weight.

After a race, both the jockey and all racing gear-saddle, tack, and saddlecloth-are weighed. If a rider is under the minimum, the mount is disqualified; if they are overweight, racing continues though with possible penalties. Apprentices and conditionals can claim weight allowances, which are gradually reduced as they rack up wins.

Different regions offer variations: for example, female riders in France receive a gender-based weight allowance, which can be advantageous in tightly-matched competitions.

Flat Race and Steeplechase Weights Differ Dramatically

The stakes of weight are even more evident when you separate flat racing-run on level ground-from jump racing (National Hunt), where obstacles are involved. Jockeys in flat races may weigh as little as 108lbs (49kg) including gear, and horses rarely carry more than 140lbs (63.5kg) total.

In contrast, jump jockeys operate under higher weight minimums: 10st (63.5kg) is the usual lower limit, escalating up to 12st 7lb (79kg) in some events. They often use special saddlecloths lined with lead to adjust as needed. Though these restrictions are less grueling for taller or older jockeys, injuries are more common due to the demands of jumping, making longevity a mixed blessing in this field.

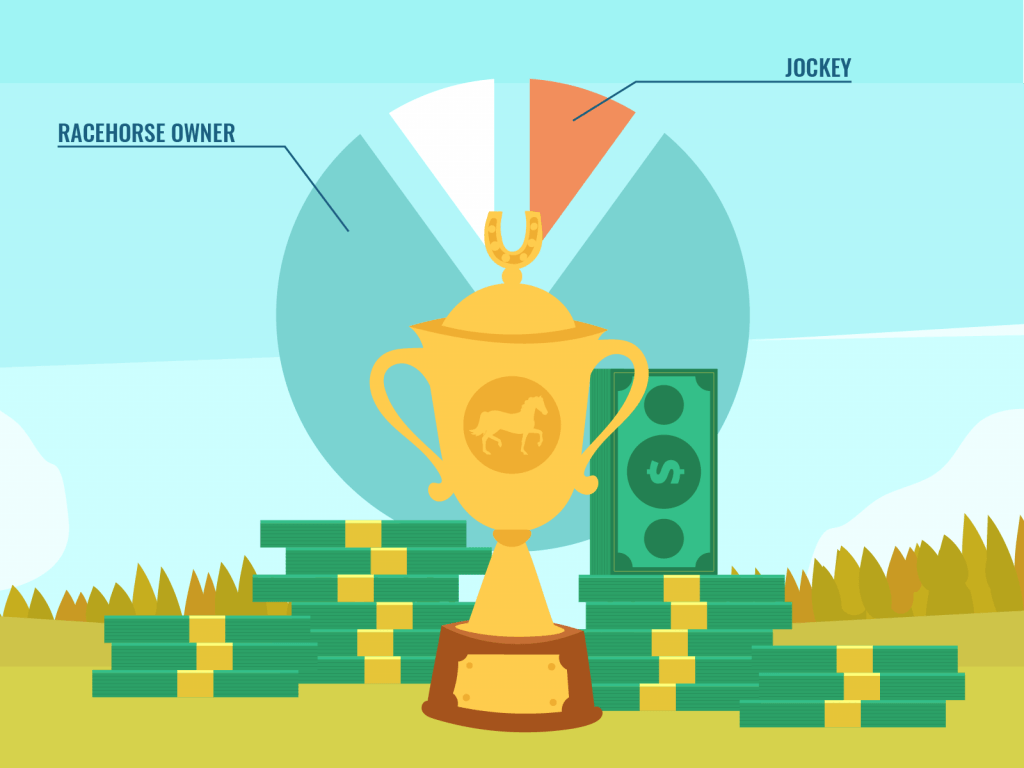

Jockeys Take Home Less Than 10% of Prize Money

Despite their risks and responsibilities, jockeys do not earn as much as many expect. In jump racing, they typically receive around 8-9% of the winnings; on the flat, the standard is even lower, generally less than 7%. The vast majority of prize money-about 80%-goes to horse owners, with smaller shares for trainers and stable staff.

Placed finishes earn even less, usually just 3.5%. Additional earnings are further reduced by agents’ commissions and other deductions, and jockeys are not compensated when out injured-making financial security an ongoing concern in the profession.

Strict Regulations Govern Use of the Whip in Races

The use of the whip is one of the most tightly regulated aspects of horse racing. Only specialized foam-padded whips made from synthetic materials are allowed, and their use is limited to a set number of strikes per race: seven on the flat and eight over jumps. Exceeding these limits can result in substantial fines or suspensions.

The correct application is on the horse’s hindquarters, and jockeys are expected to judge when further use is not in the animal’s best interests. Racing authorities continue to collaborate with animal welfare groups to update these rules and ensure humane treatment.

Jockeys Are Strictly Prohibited from Betting on Races

To maintain integrity and prevent conflicts of interest, jockeys are not permitted to wager on races. Offenses carry severe consequences: for example, British jockey Hayley Turner served a three-month suspension for breaking this rule, while in Australia, two-year bans are mandatory for betting violations, with even harsher penalties possible.

Jockeys possess intimate knowledge of horses, stables, and conditions, which makes strong enforcement of this rule central to maintaining fair competition in the sport.

The Real Dangers: Fatalities and Life-Altering Injuries Are Part of the Job

Horse racing is inherently dangerous, despite advances in rider protection. Since 1950, over 100 jockeys in North America have lost their lives due to injuries sustained during races. Even more have experienced lasting disability, particularly from falls in jump racing.

While modern measures like compulsory helmets and lightweight body protectors have reduced the risks and fatality rates-especially in places like California-complete safety remains elusive. Nevertheless, the pursuit of greater protection for both human and equine athletes continues.

Most Jockeys’ Careers End Before Age 40

Managing race weight becomes even more difficult with age. As a result, the majority of jockeys retire in their late 30s or early 40s. Some notable exceptions-such as Lester Piggott, who returned to racing at 54 and clinched a final win at 58, and Hall of Famers like Mike Smith and Yutaka Take-prove that longevity is possible, but such cases are rare. For most, the physical toll dictates early retirement.

Gender Disparity Remains a Challenge in Horse Racing

Although female jockeys have broken barriers with remarkable achievements-such as Rachael Blackmore’s historic Grand National win and Holly Doyle’s record-breaking seasons-the sport is still dominated by men. Every major milestone by women is often recognized as a long-overdue “first,” and the number of professional female jockeys remains low.

Many women in the field report challenges with discrimination or even harassment. With a male-dominated culture among owners, trainers, and fellow jockeys, there’s pressure not to speak up. Gender equality in horse racing still has a long way to go, but pioneers continue to inspire hope for a more inclusive future.